New research: an astronomical evening

‘Astronomy, universally acknowledged the most sublime and interesting of those sciences which admit of popular illustration, is doubly valuable for its powerful influence and effect in the general improvement of the human mind.’

Horace Wellbeloved on Mr Walker’s Astronomical lecture 1826

Since my biography of Georgiana Molloy’s life was published, I’ve been working nearly full-time at other projects but the personal, passionate interest in her story never, ever goes away. My current research takes me further back in time, to the 18th century, but I allow myself the occasional pleasure of turning back to Georgiana’s world. Sometimes, it’s because I’m contacted by someone with new information to share. Sometimes, it’s because a reader asks me a question for which I don’t have an answer and I want to find one. Sometimes, new letters appear as if from nowhere, thanks to wonderful people in the past who decided to collect old mail for the postmarks and stamps. Sometimes, it’s simply that I’m sorting through paper and accidentally come across one of the many unexplored research pathways I didn’t have time to travel along while I was writing.

It means I’ve collected a growing file of new information, some of it surprising, some of it sad and some of it heartening. I have yet to decide what to do with the new research. And I’m still planning how best to share the collection of transcriptions, including the most recent that I wasn’t able to use in the book. But for now, here is a small offering for you!

This delightful new research crossed my path yesterday. It’s a small thing in one way, perhaps. Just one evening in the young Georgiana Kennedy’s life. But it shows us that she was one of the lucky women in her time, receiving a broad education and experiencing a rich life of learning that included new scientific thinking. It’s one more piece of evidence that helps to explain how she came to be such a well-informed young woman.

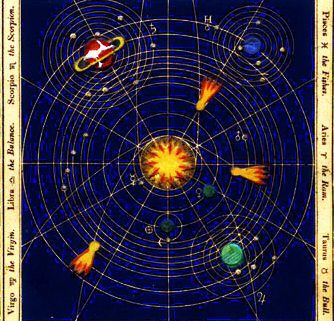

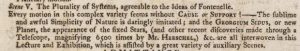

In March 1821, Georgiana attended a lecture one evening in the King’s Theatre, Haymarket, Opera Concert Room in London. She travelled there by horse-drawn carriage to see Mr Dean Walker’s presentation on astronomy. It featured an enormous contraption called an Eidouranion.

The Eidouranion showed the planets and allowed them to move in relation to the sun. It was a dramatically large mechanism that filled a theatre stage to its full height. Backlit and with a mechanical movement, it was an early ancestor of the planetarium projectors we enjoyed in the 20th century before digital lightshows.

It was more of a show than a lecture, an extravaganza. Audiences watched ‘the sublime and awful simplicity of nature, daringly imitated’. In one scene, they saw a ‘comet descend in the parabolic curve from the top of the machine and turning round the sun, ascend in like manner, its motions being accelerated and retarded according to the laws of planetary motion’.

Walker’s lectures followed on from those given by his father and elder brother in earlier years. They were acclaimed for their educational value. Georgiana enjoyed, according to the reviews, his ‘polished and easy delivery, a graceful familiarity and an elegance of diction which secures the attention of the young and unlearned’.

Images: Wikimedia Commons/Bodleian Library Digital: from the John Johnson Collection of printed ephemera