John Molloy and the emperor

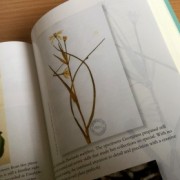

This sketch, archived among the papers of John Molloy, Georgiana’s husband who was the Government resident in Augusta and Busselton, had always puzzled me. There’s not much doubt that it’s a representation of Napoleon Bonaparte. You can read about my first thoughts here. It took a long time but earlier this year I got much closer to finding out the true story of this drawing and why it was that Molloy kept it among his personal items for so long.

I don’t know how other researchers work but, for me, it always begins with some key questions that help to focus my investigations and keep me searching in a way that’s at least vaguely logical. I knew that Molloy may well have seen the Emperor Napoleon during the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and I guessed that he himself had drawn it for his children. But what made it special enough to keep for so long? This is what I started with:

Who drew this little sketch?

Why did John Molloy keep it?

I’d already been along these pathways years before so I shifted away from the previous simple questions:

Did Molloy draw this from scratch or did he just copy another picture? Or did someone else draw it?

The first breakthrough was the new idea that this was copied from another picture, and for the first time I began using searches using only ‘images’ online.

Within an hour, I’d found several very, very similar sketches and paintings by an artist called Basil Jackson (1775-1889) all drawn from life when he was in charge of Napoleon’s household arrangements at Longwood, during the final years of captivity on the island of St Helena. Jackson made many sketches and there are also paintings, all very much alike, taken from his original life drawings. These occasionally come up for auction and one in particular, on a highly reputable online auction site in the US, was almost identical to the sketch among Molloy’s papers. (For copyright reasons I can’t include the online image here: ‘The Exile, Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte, standing small, on St Helena with Longwood House beyond inscribed beneath the mount’.)

Careful comparison of the two showed something fascinating. The sketch at the JS Battye Library in Perth WA seems to be an earlier version of the painting. But… the sketch includes more detail and, importantly, the leg position is different with an additional area of shadow that has disappeared in the painting. If John Molloy had simply copied the painting, as a complete amateur, he almost certainly would have copied it as it is and not added more detail or moved the body position. The visual evidence strongly suggests that the sketch was a precursor for the painting.

The first two questions were answered, but I had a new question. If Basil Jackson drew the sketch on St Helena in 1818, how did it come into the possession of John Molloy?

I found that Lt Col Basil Jackson and John Molloy were fellow officers at the Royal Military College at exactly the same time. A few years later, nineteen-year-old Jackson was a staff officer at the Battle of Waterloo. I read his book, his own account of those days and found something else. Not attached to an active battalion like John Molloy during the battle, circumstances left Jacklson suddenly with no superior officer and no orders so he used his initiative and spent the day riding around the battlefield passing on information to the soldiers about what was happening in other areas. He described how he came across a battalion of the Rifle Brigade and he gave their position, in the sandpit near Hougomont, the Nivelles road, exactly as the position described by John Molloy himself and in the accounts of his fellow officers. Jackson describes how pleased the men were to get his news from the battle and he says he already knew several of them. John Molloy’s good friend from the Rifles, Sir Harry Smith, describes exactly the same incident in his own autobiography.

So, another question: if John Molloy already knew Basil Jackson as a fellow army officer in 1815, how did he come to have a drawing by the same man made in 1818, after the Napoleonic Wars had ended and their careers no longer overlapped?

I try to be very careful about stating ‘facts’ when the evidence is not watertight so from here on I simply present for you the trail of information that interests me. I’ve shared these ideas with an archivist at the JS Battye library and he agrees that they probably do shed some light on how this sketch ended up among Molloy’s papers.

The watercolour painting I mentioned earlier was given to La Comtesse Bertrand, wife of Général Comte Bertrand, by Jackson himself. Bertrand and his family were living on St. Helena with Napoleon. The countess returned to England in 1821 and gave the painting to Captain Humphrey Senhouse. When he died it was part of the estate left to his daughter, Mrs Pocklington Senhouse of Netherhall, Cumberland – the same young Elizabeth Senhouse that was young Georgiana Kennedy’s close childhood friend, living just a few kilometres away and frequently visited by the Kennedy family. The two women, according to Elizabeth’s 1829 diary, were still exchanging letters frequently as adults.

There is no doubt that Elizabeth had the painting. Did she also have one or more of the sketches for it that Basil Jackson had made? In 1851 Elizabeth Pocklington-Senhouse was still living at Netherhall in Cumbria when John Molloy made his long journey to Britain after Georgiana’s death to try to conclude the details of his mother-in-law’s estate. He went to see many of Georgiana’s old friends in England and Scotland and his letters show that he stayed within a short carriage ride of Netherhall.

Did he visit Elizabeth too and talk about old times? Did he see Jackson’s painting of Napoleon on the wall and mention that he knew the man and met him again at the Battle of Waterloo? Did she offer him one of the sketches as a memento of what was one of the most memorable days of his life?

That’s the thing about research. There are always more questions.

© Photograph by Mike Rumble

JS Battye Library WA (SLWA) ACC 4730A Pencil drawing presumed to be of Napoleon with tree and cottage to the right. Anon.